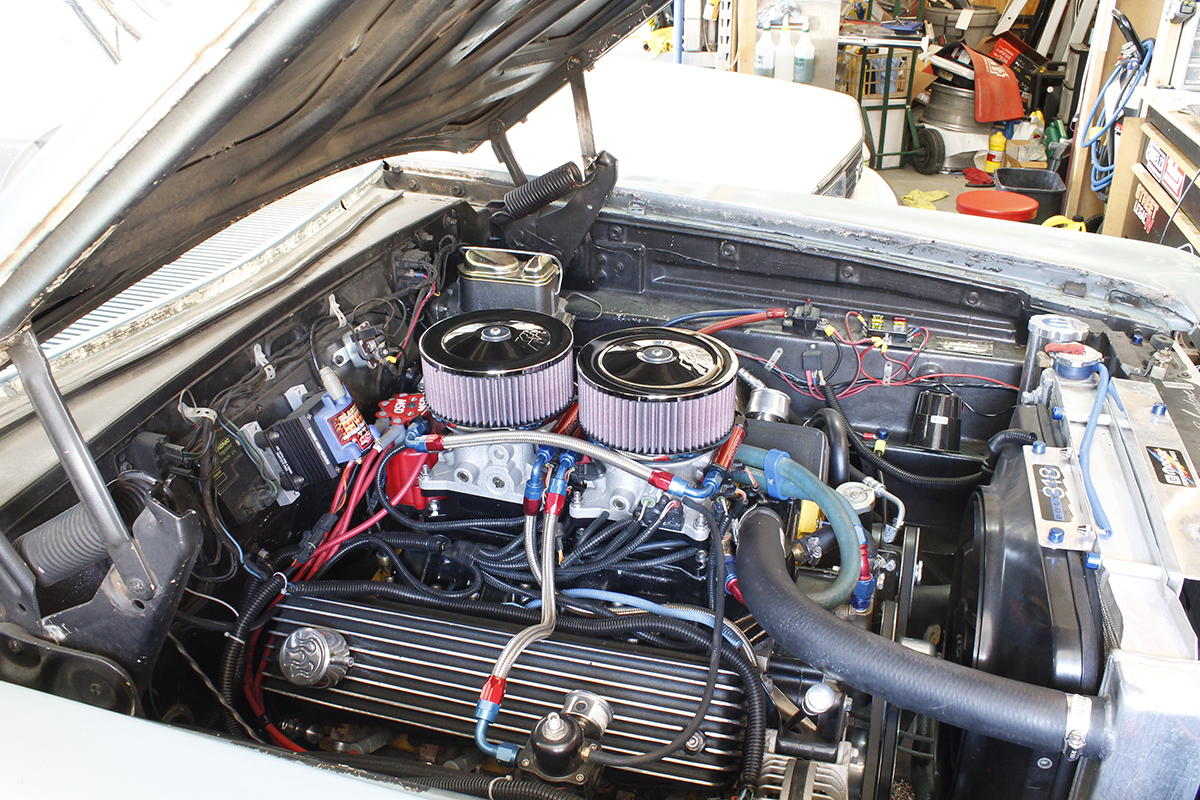

For a few years, our 1965 Plymouth Belvedere II spent time between the streets and the track, with perpetual upgrades to make the car go faster, and handle better. While many who endeavor into the world of hot rodding prefer to add the horsepower first, then beef up the rest of the drivetrain to handle it, we went the opposite direction.

We had a fairly fresh engine in our old Polyspherical 318, so we didn’t see the need to pull that engine and drop in a more powerful one just yet. Over the course of a few years, we beefed up the braking in three stages, the suspension in three stages, and toyed with various methods of fuel delivery. Once we had everything else dialed in, we were ready for more power, so we found a 1973 360ci block that a friend generously sold to us for pennies on the dollar (thanks, Jack), and started collecting performance parts to build it.

The original plan was a 408ci stroker based on that 360, but we wanted to use the more modern Magnum heads along with it. An LA block with Magnum heads is nothing new to the Mopar world, but after what we experienced with two Mopar shops left us scratching our heads. We started by heading to a local Mopar shop and asking if they could build our engine with the components at hand, and the response was, “Yeah, we’ve done them before.”

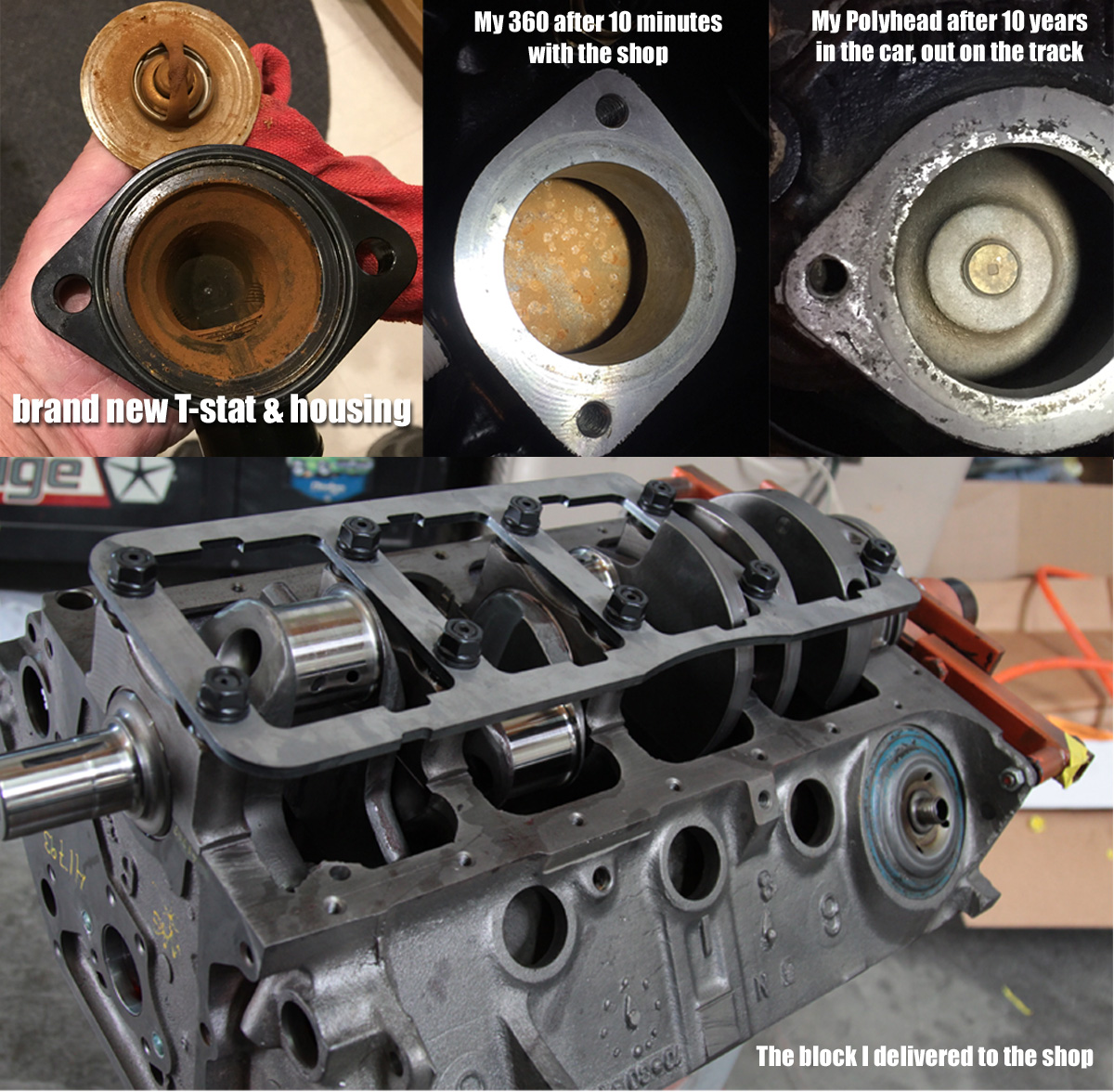

We were first quoted about $2,600, which was later upgraded to $2,900, and by the time we brought our parts in the labor was $3,300. This wasn’t a good sign, but since we felt we could trust the builder, and they were local, we agreed and the build commenced. The block had been checked for cracks and damage, and it was line bored, and the valvetrain was fitted. We were on our way to a new build with a few more ponies than our Poly was able to muster.

By the time the engine was finally done, there was a problem – a major problem. It was making a lot of noise on their run stand, to which we were told, “That’s just the exhaust leaking, the pipes aren’t tight since we’re just setting the timing and getting it running. We were sure it was a nasty valve tick, but they assured us it was okay. The long story short of it was that it was not okay, not at all.

The valvetrain clattered louder than a diesel, and the temperature climbed to over 220º on the maiden voyage. It wasn’t a good sign, so the engine came back out and it went back to the shop. it was checked again, and we were told the lifters were not working, so we bought another set, which added another $600 to the build. The engine was put together, and we were told to come pick it up. But after installing the engine a second time, we were still having overheating issues, and the valves let us know that they weren’t happy. The whole car went back to the builder a third time.

The builder looked it over, made some adjustments, and drove the car around town and filled up the tank. The call came, “The car’s ready now, you can come pick it up. Driving home, we had the same problems: valves ticking and engine overheating, we limped it home and started looking into the matter, trying to figure out why we were having so many problems. What we found out, would have anyone seeing red.

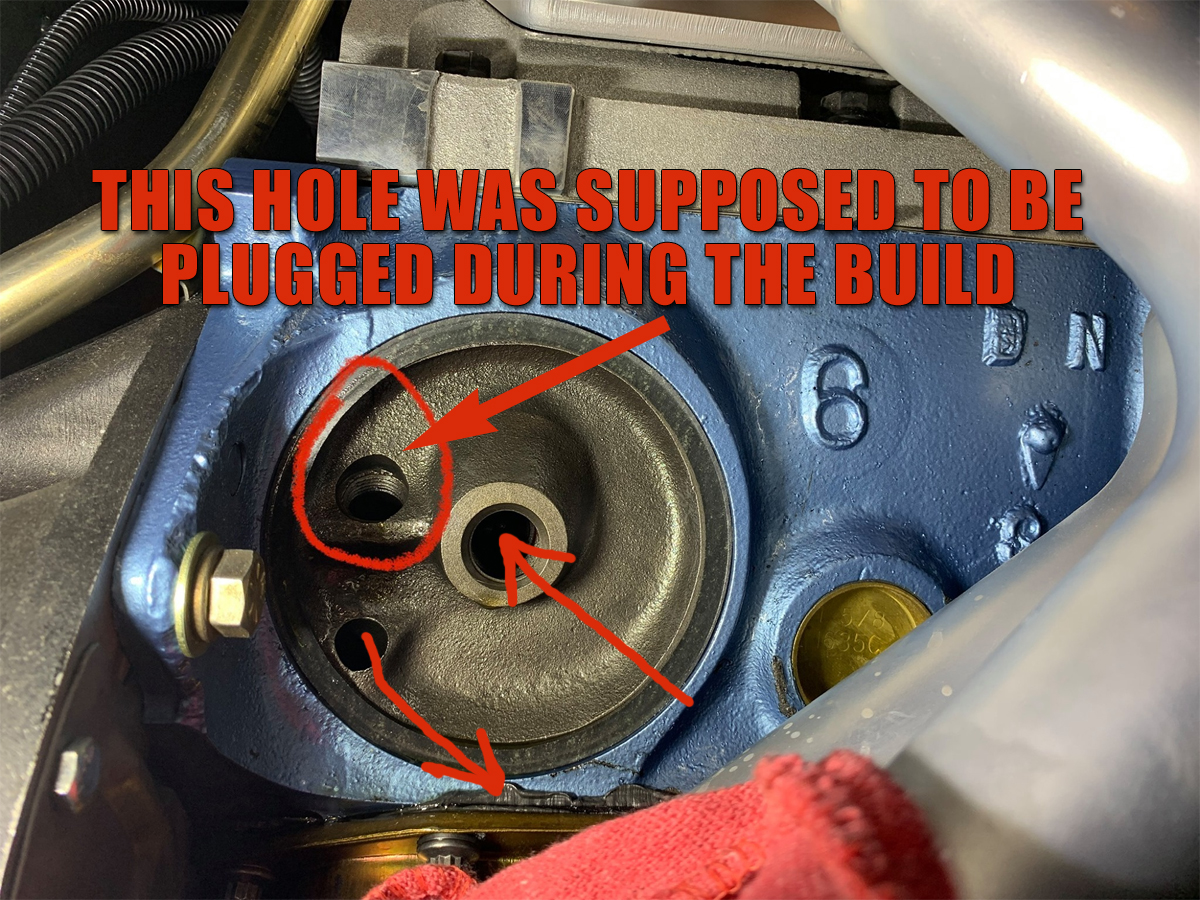

Build Failure #1

While we were trying to figure out what was wrong with our fresh engine build, we discovered a few problems that should have been caught by the local shop – especially since it’s a Mopar specialist. For starters, there is a plug that was supposed to be placed back into the block prior to the oil filter plate being installed, and the plug was missing. That meant that all of the fresh ‘start up oil’ never made it to the filter, and all of those early run shavings from the fresh build flowed through the entire oiling system. Not good.

Then we pulled a valve cover off and noticed that we had no oil whatsoever getting to the cylinder heads. Surely this was something that every engine builder would have caught, right? Not this one, not on this build. Typically, prior to installing the valve covers the engine is primed by hand to make sure oil passes through the entire engine – clearly it wasn’t checked. Our fresh build was experiencing a fresh failure, and we had to seek our money back and take it somewhere else, and start over.

The whole reason we took the engine to that shop was so it wouldn’t suffer a failure after the build, and we took it there because they are a Mopar shop. When we called to let the owner know what we discovered, the response was a very disappointing, “Well, that’s unfortunate.” It was supposed to be a simple build, one that’s been done for decades, and yet – so much failure. We got most of our money back, and sought out another builder who specialized in Ma Mopar builds.

Build Failure #2

After taking our toys and going home, we contacted another Mopar builder and we had to pull the engine apart, and start all over again. The new crankshaft needed to be polished to remove the scoring from the start up shavings, the valve guides overheated and needed to be replaced, a third set of lifters needed to be acquired, and the cylinder walls needed to be honed from where the lack of oil caused some scoring on the cylinders. How does this happen?

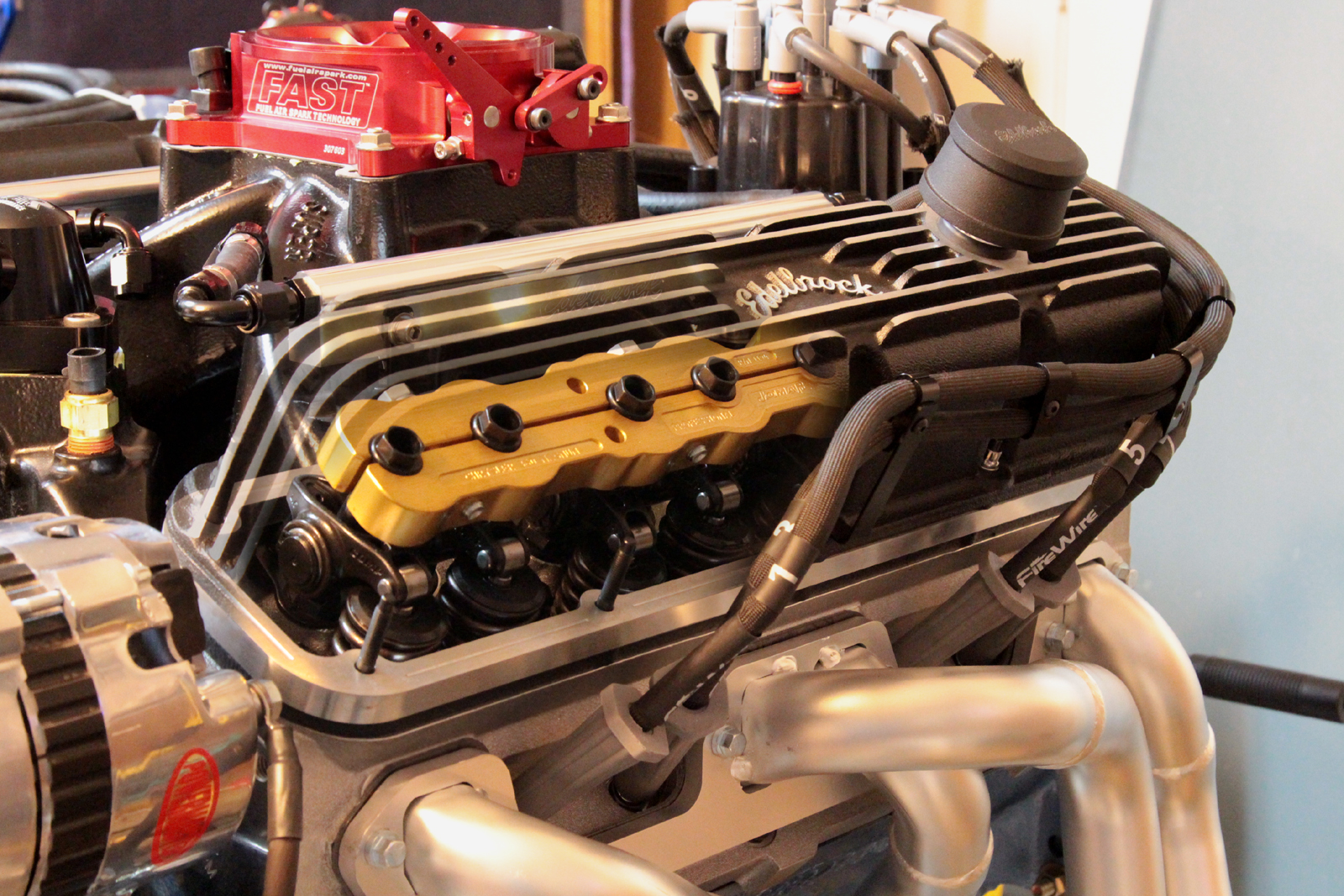

The block went back to the machine shop, where the cylinder walls were honed to remove the minor scratches, and the crankshaft was polished. Since we had to replace the valve guides, the heads went got a port and polish, and some modifications were made to the lifters to assure us that oil would be getting to the heads, this was our third set of lifters, which also meant our third set of pushrods that required sizing. Since Magnum heads are oiled through the pushrods, the assumption was that the wrong pushrods had been ordered, but they were correct. We’re still baffled at the added expenses that shouldn’t have been required.

The second build was more money than the prior build, but we needed it to run right, and after all of that time wasted with the first builder, our plans for this stroker small block were slowly drifting away. We were assured we would be happy with the build, and couldn’t wait to get it installed and then plan for the twin turbo that was supposed to be built for the project. The build was completed, then taken to get some runs on the dyno, and we were told it was ready to come and pick it up.

After installing the engine, getting all the fuel plumbed, and cleaning up the installation, we turned the key and we were immediately disappointed. The oil pump had been tested prior to the build, and it was putting out about 70-80psi; that oil pump should be reading 70psi at idle, cold; and about 30psi at idle, warm. We weren’t getting the oil pressure that we thought we’d see; instead of 70psi, the gauge was reading about 30psi, cold. When it warmed up, the pressure dropped, and immediately we called the builder. Our Dakota Digital gauges alerted us that we were getting below 10psi, in fact, we saw about 5psi, and that’s not good for a street car.

The builder tried to tell us that our gauge was reading incorrectly, so we borrowed a mechanical gauge to check the pressure: it was still about 5psi at idle, warm. The builder made all sorts of excuses, a personal favorite was, “Well you came and picked it up.” Funny, the engine was picked up from the dyno facility because he called us and asked us to pick it up there so he wouldn’t have to deal with loading and unloading the engine. The best part of all of this was that he decided he didn’t want to deal with us anymore, and stopped answering our calls – he knew that since it was during the COVID fiasco, we wouldn’t be able to take him to court, and we were essentially stuck with a $9,000 paperweight.

Why Don’t You Just Fix It?

There could be a number of issues with our fresh build: it could be an obstruction with the pump, it could be too much clearance on the bearings, or it could be something else. The builder is a drag racer, and he likes to build his small block Mopars with a lot of bearing clearance, so he may have done that with ours. Either way, it was going to cost at least another $1,000-1,500 to pull the engine apart and try to figure it out. But even if we did that, we still had another problem on our hands: the plans for the twin-turbo system were done – that ship sailed. Too much time and too many problems; it wasn’t looking good and we wouldn’t wish those problems on anyone.

That left us with a naturally aspirated build with 8.5:1 compression, and while it was pretty nice power at 427hp at the crank, it wasn’t going to be a fun car to drive because the compression was down, albeit planned. Typically, a build like this would see closer to 600hp, so even if we spent the money to figure it out, we’d still have a low compression build. It was time for plan B, and it just so happened that a local body shop had taken in a 2019 Hellcat Redeye Challenger with just 1,815 miles on the clock. The car had been rolled, and the drivetrain was up for the taking – along with some serious cash.

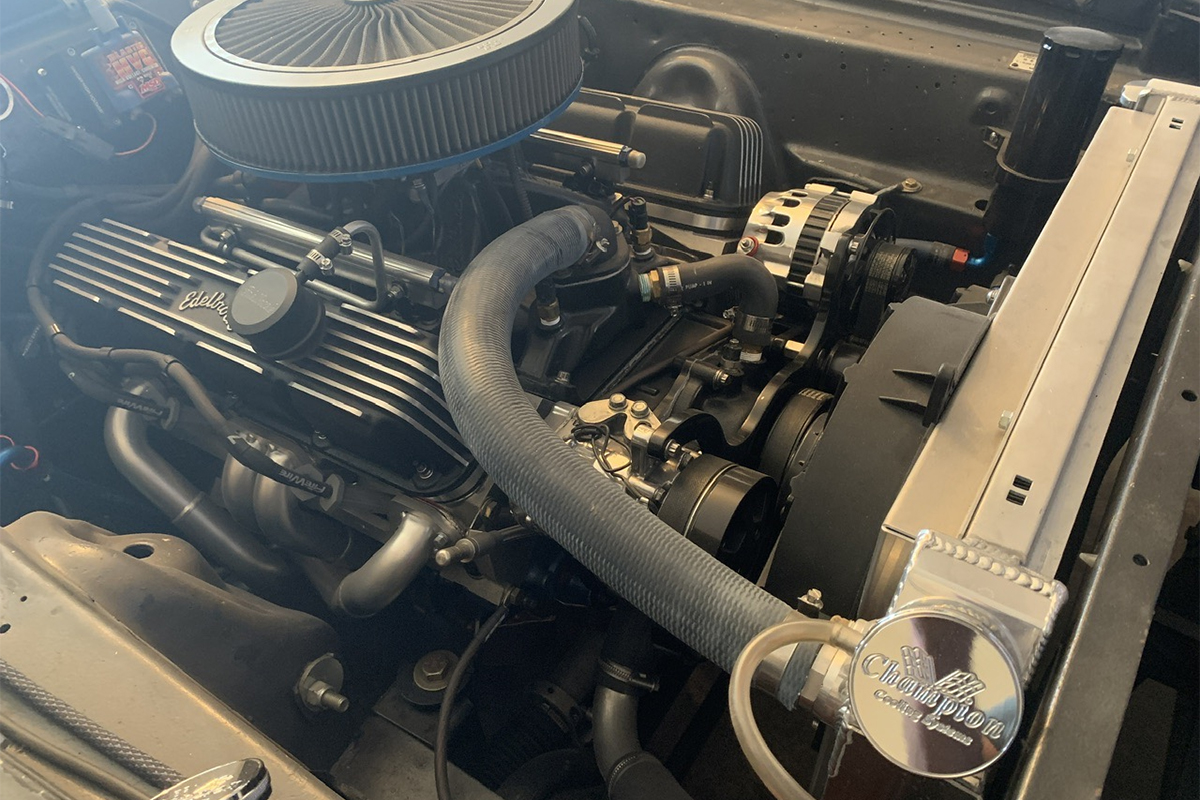

When thinking about a modern powerplant in a classic car, the Gen 3 Hemi is the Chevy’s LS swap, the Ford’s Coyote swap. The Hellcat swap, however, is just a little bit more of an attention getter, and we figured, “why not?” While you can purchase Hellcat crate engines, along with a new PCM and harness, the one thing you don’t get is the rest of the drivetrain: the 8-speed transmission, all of the oil and supercharger coolers, the coolant pump for the supercharger, the hoses, and other goodies like the cluster, radio, console, shifter, rearend, driveshaft… the list goes on. All of these goodies were there for the taking, and all for about the same cost as a Hellcrate package. We were sucked in, and thus the Hellvedere II was born.

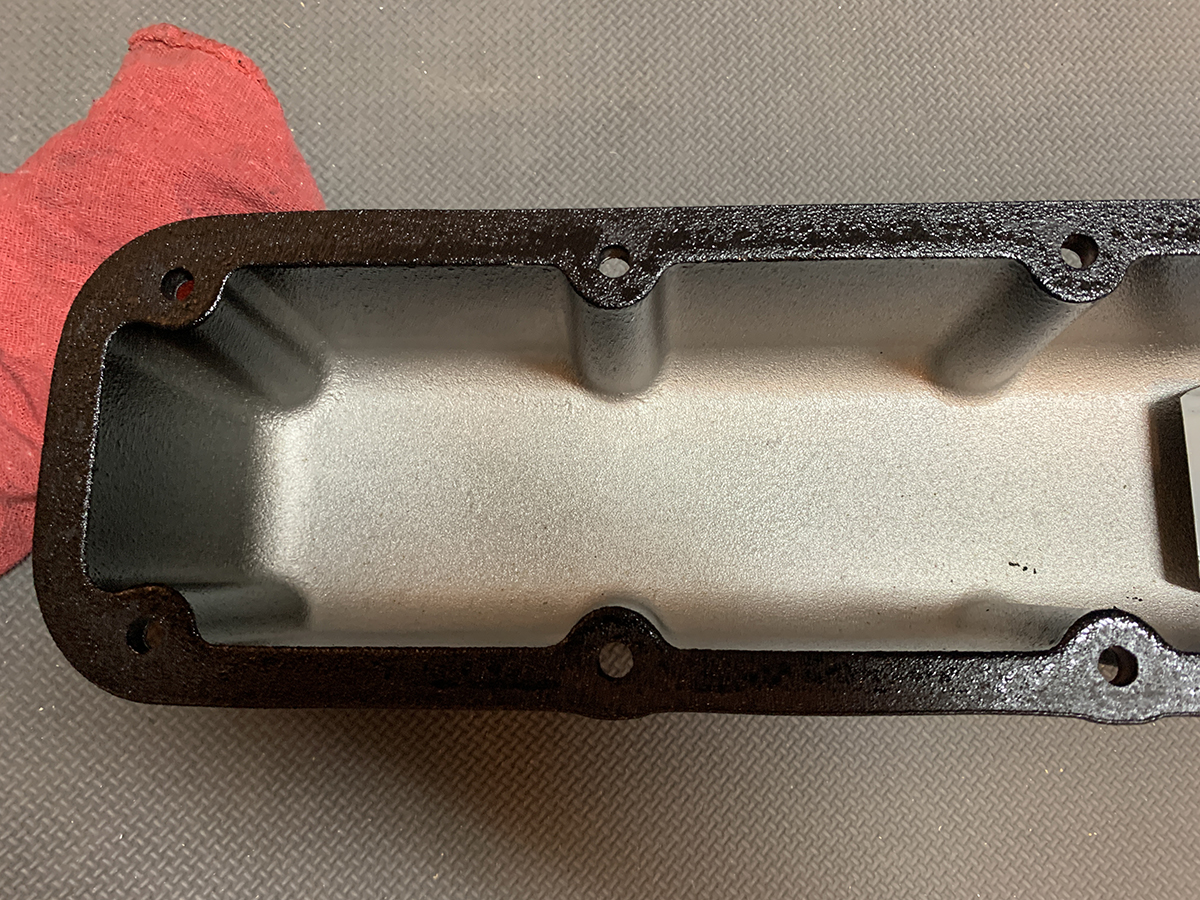

We got our engine, after a long wait due to laziness and an uncaring attitude on the part of the guy who had the car. And the first thing we had to do was clean it up. After being rolled, the engine compartment filled with dirt and such, and then after sitting for a couple of years it got a little dirtier. In the meantime, we bought our headers, PCM and harness, got out new engine mounts from Control Freak Suspensions, and we spoke with a few of our partners in the industry about this build, seeking assistance with helping to show others what’s available for a build like this. We plan to document the entire process for you here, so sit back and enjoy the ride, we’re about to embark on Project Windstorm.